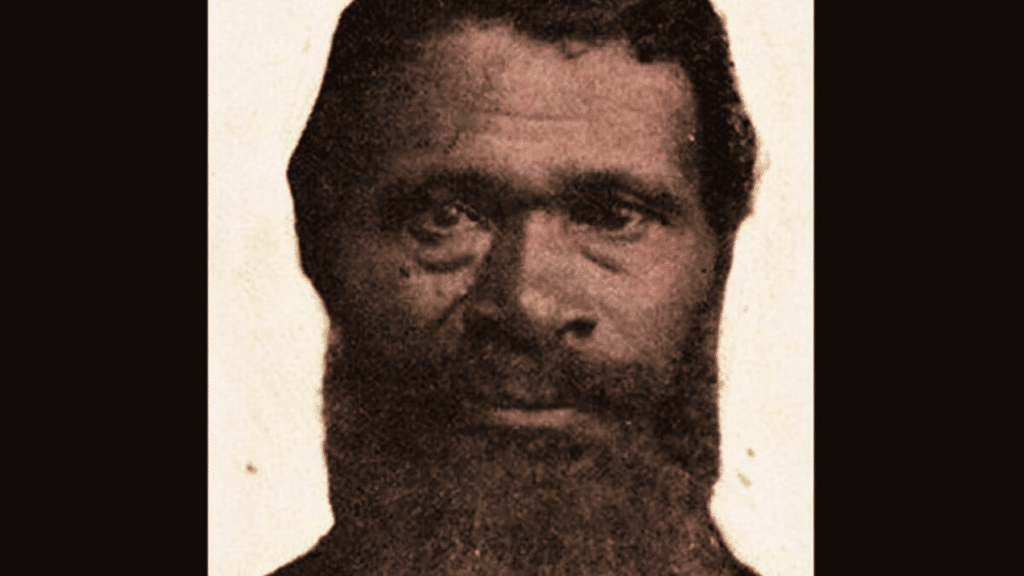

In 1825, Jordan Anderson (sometimes spelled “Jordon”), then about eight years old, was sold into slavery and spent 39 years serving the Anderson family.

When Union forces occupied the Anderson plantation in 1864, Jordan and his wife, Amanda, were freed. They later arrived in Dayton, Ohio, and in 1865, Jordan received a letter from his previous owner, Colonel P.H. Anderson.

The letter politely requested that Jordan return to the plantation, which had deteriorated during the war.

On August 7, 1865, Jordan dictated his reply to his new employer, Valentine Winters, who published it in the Cincinnati Commercial.

Titled “Letter from a Freedman to His Old Master,” the letter was amusing and filled with compassion, defiance, and dignity. Later that year, the New York Daily Tribune and Lydia Marie Child’s “The Freedman's Book” republished it.

In the letter, Jordan references “Miss Mary” (Colonel Anderson's wife), “Martha” (Colonel Anderson's daughter), Henry (likely Colonel Anderson's son), and George Carter (a local carpenter).

Dayton, Ohio

August 7, 1865

To My Former Master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Dear Sir,

I received your letter and was surprised and pleased that you still remember me and want me to return to work for you, promising better treatment than anyone else. I often worried about you, fearing the Yankees would have punished you for sheltering rebels. I also recall when you visited Colonel Martin's to confront the Union soldier left in the stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left, I’m relieved you weren’t harmed and are still alive. I would be glad to return and see Miss Mary, Miss Martha, and the rest of the family.

Please give them my regards and tell them I hope to see them in the afterlife, if not in this one. I considered visiting while I was at the Nashville Hospital, but a neighbor warned me that Henry might shoot me if he had the chance.

I’m curious about the “good chance” you mentioned. I’m doing reasonably well here, earning twenty-five dollars a month with food and clothing provided. My wife, Mandy—whom people now call Mrs. Anderson—and our children, Milly, Jane, and Grundy, are doing well. The children attend school, and Grundy is praised for his intellect. We attend Sunday school and church regularly, and people treat us kindly. We occasionally hear comments about how “colored people were slaves” in Tennessee, which upsets the children. However, I remind them that being your servant was once an honor. Please specify the wages you offer to decide if returning would be advantageous.

Regarding my freedom, which you claim I can have, I already obtained my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General in Nashville. Mandy would be apprehensive about returning without proof of fair treatment, so we request our past wages to test your sincerity. We worked faithfully for you for thirty-two and twenty years, respectively. With me earning twenty-five dollars a month and Mandy earning two dollars a week, our total earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred eighty dollars. Please deduct the costs for clothing, three doctor visits for me, and a tooth extraction for Mandy. Send the payment via Adams's Express to V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you settle our past wages, it will be easier to trust your promises for the future. We hope you recognize the injustices done to us and our ancestors by making us work for nothing.

In your reply, please confirm if my grown daughters, Milly and Jane, who are now young women, would be safe from harm and if there are any schools for colored children in your area. My greatest wish is for my children to receive an education and develop good habits.

Please also extend my thanks to George Carter for disarming you when you were shooting at me.

Sincerely,

Jordan Anderson

Learn more about Jordan Anderson here.

Skip to content

Skip to content