Researchers are continually seeking new ways to treat depression without the negative side effects or dependency issues associated with many conventional medications. While alternatives such as psychopsilocybin and ketamine have emerged, a recent innovation involves a surgically implanted brain device. For one patient, this new approach has proven transformative.

Sarah, 36, had long struggled with severe depression. According to reports from BBC and CNN, her symptoms were so debilitating that she described her daily life as torturous and found herself resisting suicidal thoughts multiple times an hour.

Having exhausted other treatment options, Sarah felt desperate for any form of relief. She decided to participate in a pioneering trial at the University of California, San Francisco, which involved testing a new brain device initially developed for epilepsy patients.

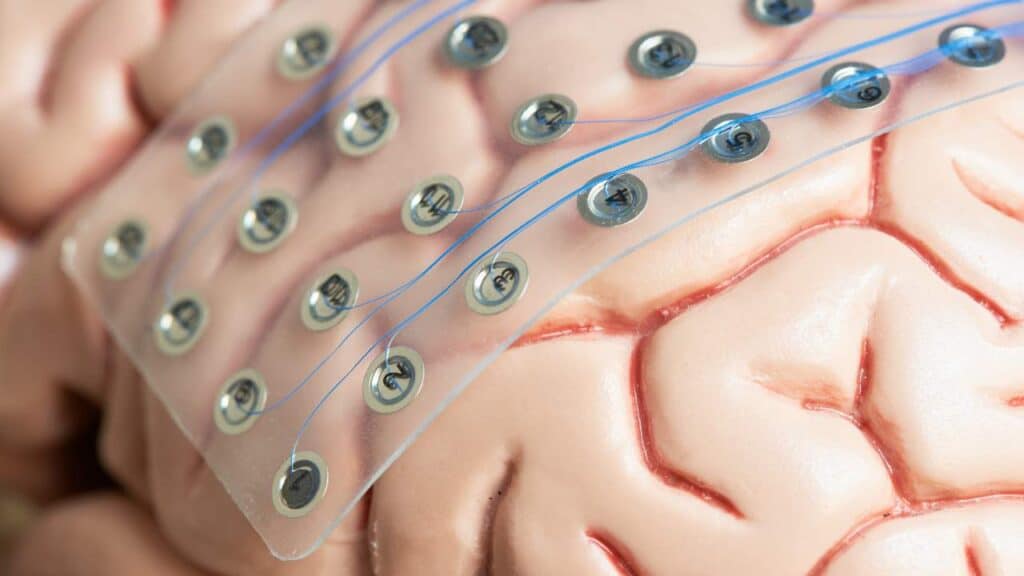

The device, roughly the size of a matchbook, required Sarah to undergo a minimally invasive but complex surgery. This procedure involved drilling two holes in her skull to insert wires for brain monitoring and stimulation, and removing a small piece of her skull to accommodate the device, which would be permanently implanted under her scalp.

The results were immediate and profound. Sarah reported experiencing euphoric feelings upon waking and found herself laughing spontaneously for the first time in years. “It was the first time I had genuinely laughed and smiled without forcing it in five years,” she said. “A wave of joy washed over me.”

What began as a glimmer of hope evolved into a significant improvement over the course of a year. Sarah's depression continued to ease without any adverse side effects, a notable achievement given that many treatments provide only temporary relief before worsening.

Reflecting on her progress, Sarah noted that her suicidal thoughts vanished within weeks, and her perception of the world gradually transformed from “gray and uninteresting” to “gorgeous and colorful.”

The research team at UCSF acknowledges that while they are still in the early stages of this treatment's development, the study highlights two key points. First, it challenges the notion that depression is a moral failing. Cognitive therapy and medication may work for some, but severe cases like Sarah's may require more specialized interventions. Just as physical ailments are not stigmatized, mental illness should be approached with the same understanding and medical attention.

Second, the study suggests that personalized treatment could soon be a reality. According to Dr. Edward Chang, a neurosurgeon at UCSF, depression affects multiple brain areas, and the device offers unprecedented precision in targeting these regions. By using data on brain activity to tailor treatments, this approach could represent a significant advancement in depression therapy.

While further testing is needed to confirm the device's long-term efficacy, this development represents a hopeful step forward for those with severe depression. In a time of skepticism toward scientific and medical advancements, it is reassuring to witness such promising progress.

Skip to content

Skip to content